History reveals that the 1960s brought a great deal of new attitudes and cultural change towards the forefront of society. Part of this history was a growing concern for the environment. The realization that problems such as raw sewage flowing into lakes and rivers, smokestacks creating unbearable smog, and the haphazard use of pesticides and other chemicals could no longer be ignored.

The news and media began pushing the environmental agenda. In 1962, Rachel Carsen published the bestselling book Silent Spring, which discussed the indiscriminate use of pesticides, specifically DDT, and its effects on the environment and people. In 1969, Time magazine covered a story detailing a fire on the Cuyahoga River, which sparked outrage. It described the Cuyahoga River, “as the river that “oozes rather than flows” and in which a person “does not drown but decays.” The river had started on fire 13 times since 1868 due to industrial pollution. Finally, the space race provided pictures of Earth, the blue planet, which heightened people’s awareness that the planet’s resources are finite. This propelled the environmental concern to the forefront of politics. As a result, President Richard Nixon decided he must address the environmental issue.

President Nixon began by creating a council to organize federal government agencies to reduce pollution. He presented a 37 point message to the council on the environment. These points included the following history:

- requesting four billion dollars for the improvement of water treatment facilities

- asking for national air quality standards and stringent guidelines to lower motor vehicle emissions

- launching federally-funded research to reduce automobile pollution

- ordering a clean-up of federal facilities that had fouled air and water

- seeking legislation to end the dumping of wastes into the Great Lakes

- proposing a tax on lead additives in gasoline

- forwarding to Congress a plan to tighten safeguards on the seaborne transportation of oil and approving a National Contingency Plan for the treatment of oil spills.

The council recommended consolidating many of the different environmental responsibilities under one new agency. On December 2nd, 1970, President Nixon formed the United States Environmental Protection Agency, commonly known as the EPA.

As history demonstrates, the newly formed EPA would institute more pollution control programs, allowing a better and more efficient response to environmental problems. The EPA began researching pollutants and their impact on the environment and establishing quantitative data that would be the basis for environmental guidelines. These guidelines were the basis for air and water quality standards as well individual pollutants. During the EPA’s formative years, it passed laws such as:

- the Coastal Zone Management Act (1972)

- the Marine Protection Research and Sanctuaries Act (1972)

- the Endangered Species Act (1973)

- the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1976)

- the Marine Mammal Protection Act (1972)

- the Deepwater Ports and Waterways Safety Act (1974)

- the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act (1974)

- the Water Resources Planning Act (1977)

- the Water Resources Research Act (1977)

- the Environmental Quality Improvement Act (1970)

The EPA also added several amendments to the Food Drug and Cosmetics Act and the Environmental Education Act as well as enforcing the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899.

The newly formed EPA’s first administrator, William D. Ruckelshaus, went quickly to work to improve the environmental standards, announcing in his first speech to the National Press Club that “Each of us must begin to realize our own relationship to the environment. Each of us must begin to measure the impact of our own decisions and actions on the quality of air, water, and soil of this nation.” A few weeks later he warned the cities of Atlanta, Detroit, and Cleveland that they had 180 days to comply with water pollution standards or there would be a federal suit against them. Atlanta was cited for allowing massive discharge of pollutants in to the Chattahoochee River while Detroit and Cleveland were cited for polluting Lake Erie and its tributaries.

Early on the EPA took action on DDT to protect groundwater and wildlife.

Pesticides, specifically, DDT, became Ruckelshaus’s next main issue due to safety concerns presented to the public in Silver Spring. At the time, DDT was the most popular and widely used insecticide in the world due to its cost, effectiveness, and versatility. However, many environmental groups wanted it banned such as the Environmental Defense Fund, the Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation, and the Izaak Walton League.

Initially, Ruckelshaus rejected the idea of banning the pesticide since EPA’s internal staff stated DDT was not an imminent danger, but these studies were criticized since they were conducted by the United States Department of Agriculture. Therefore, the EPA held seven months of hearings in 1971-72 with scientists presenting evidence for and against the use of the pesticide. In 1972, the EPA banned most uses of DDT to protect groundwater and wildlife, exempting public health uses under some conditions. The following year, the EPA’s first administrator, William Ruckelshaus left to become the director of the FBI.

Future EPA administrators would continue his fight to protect the environment. In December of 1974, the EPA passed the Safe Drinking Water Act. Before this act, state and local governments managed its own drinking water quality. The Safe Drinking Water Act was federal law that defined roles and responsibilities as well as used scientific standards used to protect public drinking water. The act does not pertain to private wells. It also aimed to control underground injection of wastewater and even the injection of clean water that would provide a conduit for contaminants.

In March 1977, in response to the Love Canal disaster, the EPA focused on hazardous waste disposal and its contamination of land and aquifers. From the 1940s through the early 1950s, the Hooker Chemical Company buried over 21,800 short tons of chemicals on the Love Canal property before selling it to the Niagara Falls City School District, where ultimately two schools where built. Adjacent to the property, home builders developed low-income and single family residences.

In the early 80’s and 90’s buried drum disposals were of great interest.

For years, residents were suspicious of the black fluid and odiferous substances that flowed out of the canal. In 1976, two reporters from the Niagara Falls Gazette tested several sump pumps near Love Canal and found toxic chemicals in them. Further, another reporter found that there where an abnormal rate of birth defects, anomalies, and miscarriages in the area. These reports led to the activism behind the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), better known as the Superfund Act enacted in 1980.

The Superfund Act funds the cleanup of sites contaminated with hazardous substances and pollutants. Since 1980, the EPA’s Superfund program has helped protect human health, groundwater, and the environment by managing some of the nation’s most significant environmental emergencies including the Love Canal disaster, Kentucky’s Valley of Drums site, the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the September 11th World Trade Center disaster site, and the clean-up response to Hurricane Katrina.

In the late 1980s, the EPA, learning from disasters in past history like Love Canal, began to issue strict, comprehensive requirements for nearly two million underground storage tanks, half of which stored fuel for gas stations. Prior to the mid 1980s, most underground storage tanks, or USTs, were made of bare steel, which corrodes over time, resulting in ground water contamination.

After drum disposals, the focus moved to buried underground storage tanks and groundwater contamination.

The UST program’s main goal is to prevent and clean any leaks or spills from underground storage tanks. Since prevention is easier and more cost effective than clean-up of petroleum products, new storage tanks were designed to prevent corrosion, spills, and overfilling. Further, a record of the tank’s location is now better maintained since many times an old tank’s location and/or removal was not well documented, resulting in timely and expensive site surveys. Once a tank reached its end of life, it needed to be closed properly and removed from service.

Much like the UST program, the EPA asked state agencies to monitor privately owned septic tank systems also known as decentralized wastewater treatment facilities. These systems possess a tank, allowing settleable solids to settle to the bottom while floatable solids (oil and greases) rise to the top. Obviously, tanks need to be watertight and stable. From the tank, the wastewater enters a sewer or is

passed directly to a treatment system. As much as 25% of all homes possess a decentralized wastewater treatment system. Unfortunately, up to 10% of these systems have wastewater emerging on the ground surface and more than half the systems are older than 30 years old and beginning to fail. To combat this, the EPA asks the state to enforce regulations and inspect private septic systems regularly.

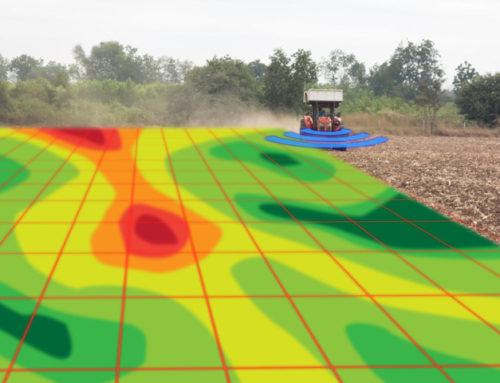

Presently, the EPA and state governments are focusing on groundwater contamination from excess nutrient loading from farms. Of great concern are nitrogen and phosphorous from cropland fertilization as well as biological contaminates from animal waste. For example, in 2014, a massive bloom of cyanobacteria (green-blue algae) in Lake Erie fueled by farmland nutrient runoff caused the closure of water facilities that serves over 500,000 people in Toledo, Ohio. Meanwhile in Wisconsin, Kewaunee County requested emergency action by the EPA to address its groundwater issues from manure runoff that contaminated surrounding water wells. This resulted in the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources creating a Groundwater Collaboration Workshop to provide recommendations for short-term solutions, best management practices, compliance regulations, and communication procedures.

EPA requires the State of Wisconsin to regulate farmers and agricultural facilities.

Currently, the EPA has passed scientifically-based maximum daily load standards for fertilization and manure spreading and asked state governments to develop nutrient management plans and manure spreading regulations to prevent groundwater contamination. Many farming states like Wisconsin, where shallow karst bedrock provides a direct conduit to its water table, are scrambling to create cost effective solutions to prevent future groundwater contamination from nutrient management and manure spreading while allowing farmers to successfully grow their crops and raise their animals.

Today there is little surprise that farms and agricultural facilities are a concern for groundwater contamination.

Wisconsin developed regulations as to where and how much manure a farmer spreads on a piece of land relative to the depth of bedrock in counties of concern, but has yet to answer how it will survey such properties and evaluate farms, large and small, for compliance. Ultimately, groundwater protection in relation to farms and agricultural facilities remains unsettled. While it is hard to state what lies in the future regarding plans to remediate polluting farming practices, the past suggest that the solution lies in preventing contamination before it happens, meaning that best practices need development to survey land and assess it for nutrient and manure spreading.

History shows that the problem of groundwater contamination has created vast regulations.