Without doubt, any definition or discussion about Silurian bedrock in Wisconsin would have its roots in other people’s work. Consequently, here are fragments of text others have written about the Silurian geologic period and how it pertains to Wisconsin. The educational material provided by the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey is from the University of Wisconsin Extension. The abstract presented by M. G. Sherrill is very interesting, since it talks about the potential for groundwater contamination in the late 1970’s. Click here to learn by Silurian bedrock is important to farmers and agricultural facilities.

Silurian From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

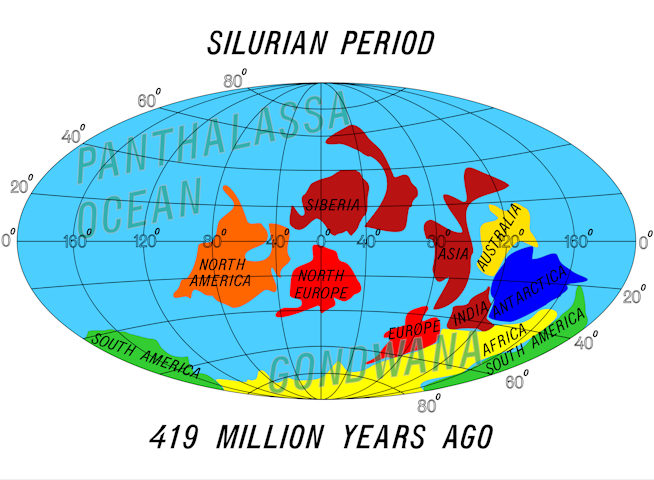

The Silurian is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at 443.8 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, 419.2 Mya.[8] As with other geologic periods, the rock beds that define the period’s start and end are well identified, but the exact dates are uncertain by several million years. The base of the Silurian is set at a series of major Ordovician–Silurian extinction events when 60% of marine species were wiped out.

A significant evolutionary milestone during the Silurian was the diversification of jawed fish and bony fish. Multi-cellular life also began to appear on land in the form of small, bryophyte-like and vascular plants that grew beside lakes, streams, and coastlines, and terrestrial arthropods are also first found on land during the Silurian. However, terrestrial life would not greatly diversify and affect the landscape until the Devonian.

GEOLOGY AND GROUND WATER IN DOOR COUNTY, WISCONSIN, WITH EMPHASIS ON CONTAMINATION POTENTIAL IN THE SILURIAN DOLOMITE

By M. G. SHERRILL

ABSTRACT (1978)

Door County is in northeastern Wisconsin and is an area of 491 square miles. The county forms the main body of the peninsula between Green Bay and Lake Michigan. The land surface is an upland ridge controlled by the underlying bedrock. The west edge of the ridge forms an escarpment facing Green Bay.

Silurian dolomite is the upper bedrock unit throughout most of the county and is the most important aquifer. This bedrock is exposed in much of the county, particularly north of Sturgeon Bay, elsewhere, it is covered by a generally thin mantle of soil or drift.

The bedrock units are divided into two major aquifer systems in Door County; the Silurian dolomite aquifer system and the sandstone aquifer system, consisting of Ordovician and Cambrian bedrock units. These two major systems are separated by the Maquoketa Shale of Ordovician age, a nearly impermeable, generally nonproductive unit. The Silurian dolomite aquifer system is itself divided into the Niagaran aquifer and the underlying Alexandrian aquifer.

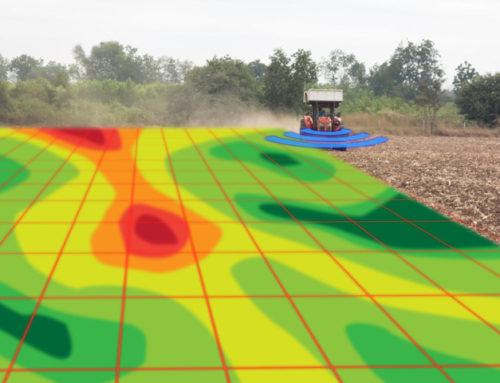

Water occurs in the Silurian dolomite aquifer system in two types of openings nearly vertical joints (fractures) and horizontal to slightly dipping bedding plane joints. Vertical joints are more common in the upper part of the Niagaran aquifer. These yield small amounts of water to wells. Bedding plane joints transmit most of the water in the lower part of the Niagaran aquifer and in the Alexandrian aquifer. The bedding plane joints, because they are poorly interconnected, act as semiartesian conduits separated by impermeable rock. Eight waterbearing zones in generally continuous bedding plane joints have been mapped.

The dolomite is recharged from direct precipitation and snowmelt. It discharges water to pumping wells and by natural springs discharge to Lake Michigan and Green Bay and to interior lakes and streams.

Wells in the Silurian dolomite aquifer system have adequate yields to meet most needs, except in the southwest corner of the county, where the dolomite is thin or absent. Transmissivity values range from a low of 4.0 feet squared per day in the Niagaran aquifer near Sturgeon Bay to more than 13 000 feet squared per day for the Alexandrian aquifer near Fish Creek.

Water from Silurian dolomite is a very hard calcium magnesium bicarbonate type, with objectionable concentrations of iron and nitrate in water from some wells. Sanitary quality, as indicated by tests for total coliform bacteria, has been a chronic problem in certain areas. Concentrations of indicator organisms are greatest during or immediately after rapid groundwater recharge, with concentrations rapidly decreasing after periods of recharge. Wells close to septic systems and in areas underlain by fractured nearsurface bedrock have the greatest incidence of contamination. The type and thickness of unconsolidated material has a direct effect on the entry of bacteria into the groundwater system. Bacterial attenuation increases with increasing soil depth and reduction in soil permeability. After bacterial contaminants reach the water table within fractured bedrock, little attenuation occurs, and the contaminants can travel long distances in a short time.

Ground water of good sanitary quality but exceeding recommended limits of the U.S. Public Health Service for sulfate and chloride is probably available from the sandstone aquifer by drilling wells 700 to 1300 feet deep.

To minimize the possibility of obtaining contaminated ground water, well construction should include properly locating the wells upgradient and as far as practical from contamination sources, setting and pressure grouting well casings to an adequate depth into firm bedrock, and casing the well into the zone of saturation.

Exposed dolomite along Lake Michigan Shoreline in Door Co.

From the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey

In eastern Wisconsin, the uppermost bedrock is mostly a carbonate rock called dolomite, and these rocks form the eastern dolomite aquifer. This aquifer is also sometimes referred to as the Silurian aquifer or the Niagaran aquifer.

The eastern dolomite aquifer extends in Wisconsin from Door County in the north, where the dolomite forms cliffs along Green Bay, along the east shore of Lake Winnebago, to the Wisconsin-Illinois state line, and to Lake Michigan on the east. In places, especially in the northern counties, this rock is exposed at the surface; in some places, especially to the south, it is covered by hundreds of feet of glacial deposits. This aquifer is thickest along the Lake Michigan shoreline, and thins to the west. It is not present in other parts of Wisconsin.

The rocks forming the eastern dolomite aquifer are about 416 to 444 million years old. This aquifer lies above a fine-grained layer of shale (this layer is called an aquitard because it restricts movement of water between aquifers). The shale protects the underlying sandstone aquifer from contamination originating at the land surface.

Dolomite aquifers produce water from interconnected cracks, fractures, and pores, and sometimes even caves. The amount of interconnection varies across the aquifer and, for that reason, the yield of wells in the eastern dolomite can vary widely—even from one well to the next.

The eastern dolomite aquifer is especially vulnerable to contamination from the surface where the cover of glacial materials is thin. In addition, groundwater is transmitted quickly through cracks that can extend from the surface to nearby wells so contamination can move rapidly through this aquifer.

Location of land masses during the Silurian period.